On Tuesday, we launched a developer preview of the Mozilla Apps project, something I’ve been working on for the better part of the year. We released a suite of tools and documentation aimed at helping developers write, deploy and sell apps built using modern web technologies like HTML5, CSS and JavaScript. Many others have already covered the question of “why” we are doing this: all the major app ecosystems out there are closed, tied to a single vendor, and could certainly use a healthy dose of the openness. There are many great things about Apps, and many great things about the Web, and we want to bring them together.

In this post, I want to cover the “how”. If you’re interested in writing apps, I would point you to the documentation we have on how to build them. On the other hand, if you’re curious to learn about how the system works as a whole, read on! A lot of different pieces of technology had to come together to get where we are today.

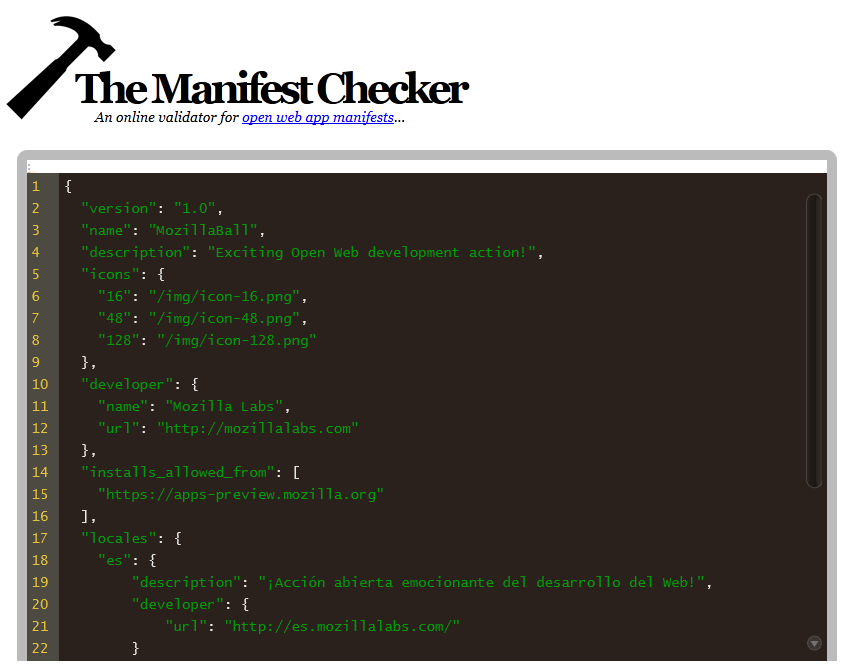

App Manifest

A fundamental building block of the system is the app manifest. Every app in the system is represented by this JSON file, documented here, which essentially contains a set of metadata about your app: name, icons, localized descriptions and so on. This manifest file is hosted at the same domain as your app. An app is uniquely identified by the domain it is hosted at, and this manifest must be served off the very same domain (at any path), with the Content-Type header set to application/x-web-app-manifest+json. We’ve received a lot of feedback stating that this is limiting, but unfortunately almost every security knob in browsers is tuned to the domain of a given page. Because we anticipate that apps will, at some point, be able to request access to elevated privileges (to use the computer’s web camera, for example), we must restrict ourselves to one app per domain. Note that app1.example.org and app2.example.org are different domains but example.org/app1 and example.org/app2 are not.

There are many other specifications that express ideas similar to this concept of a manifest (W3C Widgets, Chrome Web Store, etc.), and we are definitely very keen to standardize the format.

API: mozApps

The next piece we introduce are a set of new DOM APIs, present under the navigator namespace. The API offers a few different functions, but the most important one is navigator.mozApps.install. This function allows a web page to initiate the “installation” process for an app, which is identified by the URL to its manifest (explained previously). Any page is able to invoke this function, so you can self-publish your apps! Just add an “Install” button to your site and call this function with the right arguments. The API also provides a function that can tell if your app is currently installed (amInstalled).

There is another set of APIs under the navigator.mozApps.mgmt namespace. These “management” functions are only available to certain privileged domains, and are able to query the DOM for a list of all apps the user has installed, launch any given one, and uninstall an app. This API is expected to be used only by web pages that the user has explicitly authorized as being able to manage their apps on their behalf. We call such web pages “Dashboards”, and we built a default one into the system (which I shall explain shortly).

The mozApps API is fully documented, but you should note that as with any early DOM API (that we hope to standardize), it is subject to change. In fact, we’re already thinking about how we can further simplify the API and make it more standards-friendly. Join the discussion!

HTML5 App Runtime

Now, what actually happens when somebody calls a function described in the mozApps API? We’d like for users to be able to look for, install and launch apps from any standards-compliant browser without having to do anything special. So, we’ve built a fully in-content implementation of the mozApps API, provided by include.js that is served off the myapps.mozillalabs.com domain (the reason for that will become apparent when we discuss dashboards). Just include that JS file in any page that uses the mozApps API and you should be good to go! This applies to self-published apps as well as stores.

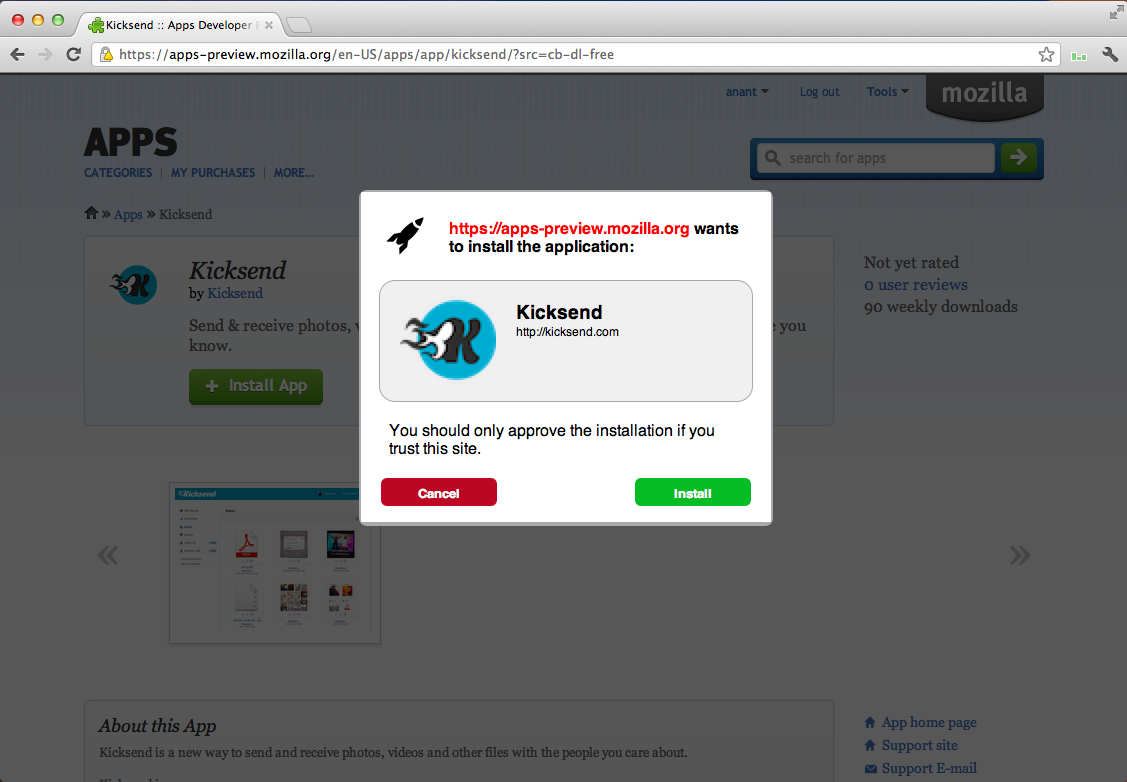

Now, whenever the install method from the mozApps API is invoked, the user is greeted with a dialog asking them to confirm if they’d like to install the app:

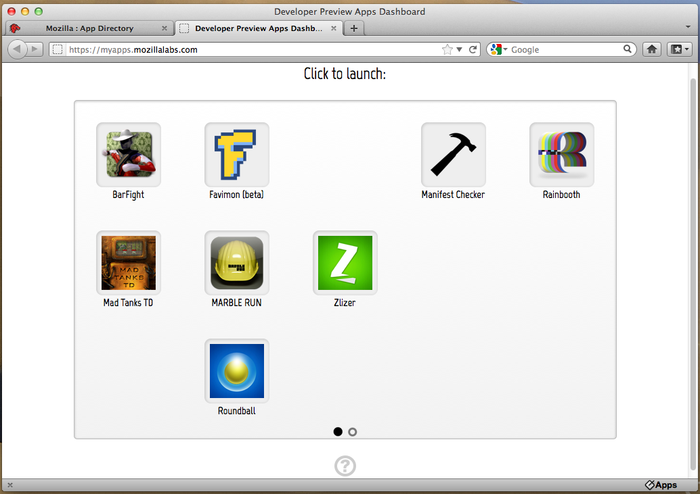

The Dashboard

Let’s say the user confirms the installation, what next? After a set of sanity checks against the manifest of the app, it is officially installed into the users collection of apps, which we call a repo. A Dashboard is the piece of software that is responsible for letting the user manage their repo, by allowing them to launch and uninstall their apps. Recall that the mozApps.mgmt set of APIs allow a dashboard to do this, and currently the myapps.mozillalabs.com domain is white-listed. In the future we expect people to write dashboards (which is essentially an app to manage apps!) that users can authorize. When a user visits the default Mozilla Labs dashboard, they look at something like this:

We implemented a touch friendly dashboard that works on both mobile devices and the desktop, to let you re-arrange your app icons and organize them in pages. This part of the dashboard is implemented using the wonderful icongrid library, which you are more than welcome to re-use while writing your own dashboard!

Clicking on an icon will launch that app. What does launching mean? In the HTML5 app runtime, it means it will open up the app in a new browser tab. However, we’ve also been experimenting with how we can improve this experience, which we will discuss next.

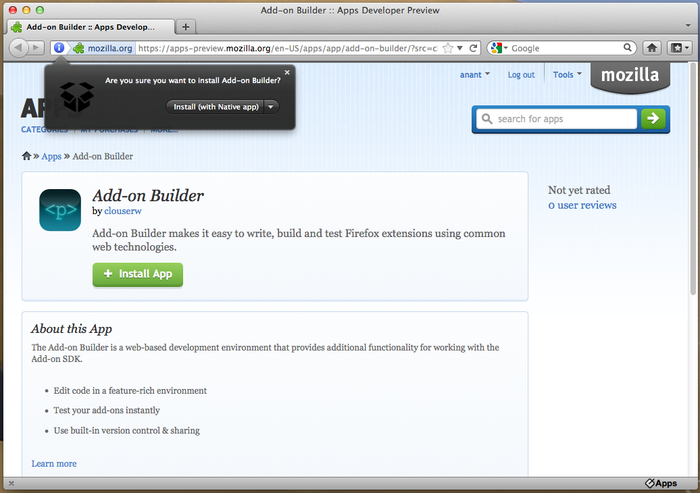

App Runtime for Firefox

For Firefox users, we have the opportunity to provide enhancements to the whole app installation and launch process while we wait for the API to get standardized. We’ve written an add-on that implements the mozApps API, which will override the _include.js _HTML5 runtime version (so stores are encouraged to continue including the include.js version to provide the most portable experience for their users). If you have this add-on installed and install an app from any page or store, you will be greeted with a doorhanger that asks you confirm if you really intend to install this app:

Note that there’s an extra option in there that asks if you want to install the “native” app version or not. On Windows and Mac, this means that we will automatically generate a .EXE or .APP that wraps your web application into a shell that looks and feels like a real app! For example, on the Mac, we will create a menu bar and dock icon for you:

Cool? Sounds pretty familiar to the Prism experiment, right?

In addition to this style of “native” launching, users can also use the dashboard from before as usual. Launching from the dashboard will open it in an app tab, a nifty little Firefox feature.

App Runtime for Android

An important feature of Apps written using web technologies is that they can work on a variety of different devices. We want users to be able to buy an app only once and use it not only on their desktop, but also on their tablets and phones. We’re going to start out with Android (iOS has its own set of tricky technical and policy problems to deal with), by introducing an App Runtime (codename “Soup”).

The App Runtime for Android is a native Android application that lets users install, launch and manage their apps just like on the desktop:

Installing an app on Android using Soup will create an icon in your home screen, tapping on it will launch the app using our embedded web runtime. Well built web applications can now look and feel just like native android apps!

In addition, apps that you installed on the desktop can be automatically synchronized to your phone (and all your other devices) using our Sync functionality, which we will discuss next.

Sync

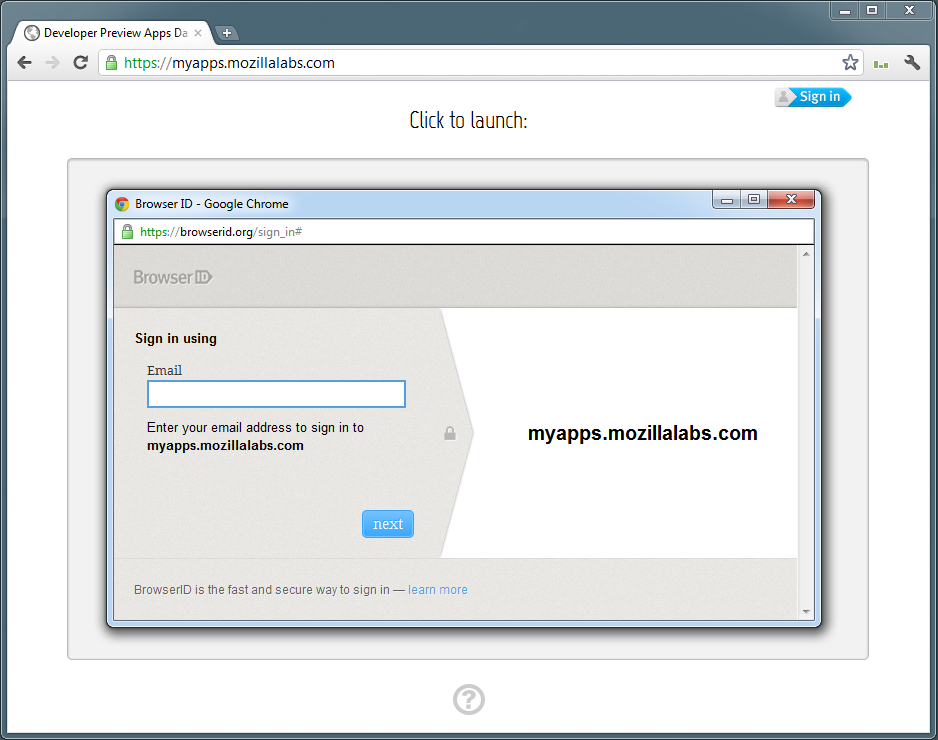

Users shouldn’t have to install apps on every device they own once they’ve purchased it. We’ve developed an AppSync solution for the HTML5 runtime, Firefox runtime as well as Android. In all three environments, you should be prompted to login with your BrowserID (Mozilla’s new federated & distributed Identity system) when you visit the dashboard:

Once you’ve logged into your dashboard, your apps from all your devices should start automatically synchronizing!

App Marketplace

Search is a great tool for the web, and we expect that many users will discover apps using search engines. However, directories have their place and are an invaluable tool to create a community around apps. Mozilla has been running addons.mozilla.org (AMO) for a while now, an easy place to find, install and review add-ons for Firefox. We want to build a similar store for Apps, and as part of the developer preview, we launched apps-preview.mozilla.org. This preview of our “app store” lets developers submit an app by telling us the link to their manifest (the process is very similar to how you submit an add-on for inclusion on AMO). Once the application is accepted into the store users can find, install, review and provide ratings for apps. This store uses the same mozApps install APIs we discussed earlier, and we expect that others will build their own stores. We want competition in the app store market too!

Supporting developers who want to sell apps is also important to us. We’re testing integration with Paypal as part of the developer preview, which will allow developers to sell apps across the world at various price tiers.

Receipts

How do we balance the need for developers to be able to charge for their apps, while allowing users to use an app they’ve already paid for across all their compatible devices? We’ve devised a receipt format that helps achieve this. When a user completes the payment process on a given store, the store will generate a receipt of this format and pass it to the mozApps API as part of the install data provided to the install call. The implementation responsible for providing the API will stash the receipt along with the app itself (and all devices the app is synced to).

At launch time, the app can ask for the receipt associated with itself using the amInstalled API call, do an integrity check, and send it over the original store that issued the receipt. The store can then verify that the receipt is indeed valid and notify the app, at which point the app can decide whether to let the user run it or not. We’ve provided a utility function verifyReceipt to help the app developer do all of this.

Do note, however, that this whole scheme is merely intended to help developers who don’t want to setup their own payment systems. Developers are free to write apps that use their own (or 3rd party) payment or subscription services. You could, for example, sell your app for free on the AMO store, but ask users to login when the app is launched, or implement your own in-app purchasing system. We will do what we can to help, but in the end, you’re in full control of what your users see when they launch your apps!

What’s next?

This is just the beginning, we have a lot more work to do before we can realize a flourishing and open app ecosystem for the web. Here are just some of thing we have planned for the next few months:

-

Building out a “Web Runtime”, or WebRT. We’ve built an initial prototype of how such a runtime might work in the add-on for Firefox, and we want this to extend this to a more robust system with auto-updates and deeper OS integration.

-

Capabilities. In conjunction with the WebAPI project, we want to provide apps with more device APIs and capabilities than regular web pages, while giving the user an easy way to control and hand out permissions. This includes things like camera access, filesystem APIs and more.

-

Web Activities. A while ago we release a prototype of the apps extension that supported what we call web activities, a way for apps to communicate with each other safely and easily. You could use this, for example, to upload a picture to a site from your favorite photo service, or to share a link from an app to all your friends using your favorite social network. The Firefox Share add-on already relies on web activities to do the latter.

-

Push sync & notifications. We want users to be able to “push” apps to any of their devices directly from an app store.

-

Standardization. It is critical for the health of the web for all of these app related APIs to be standardized and supported by all interested parties.

Most importantly, we want you to get involved and help us build!

Show me the code

I’ll end this post with a brief description of all the code behind the various pieces in hopes of attracting contributors. All of our code is hosted on Github and licensed under the MPL/GPL/LGPL tri-license.

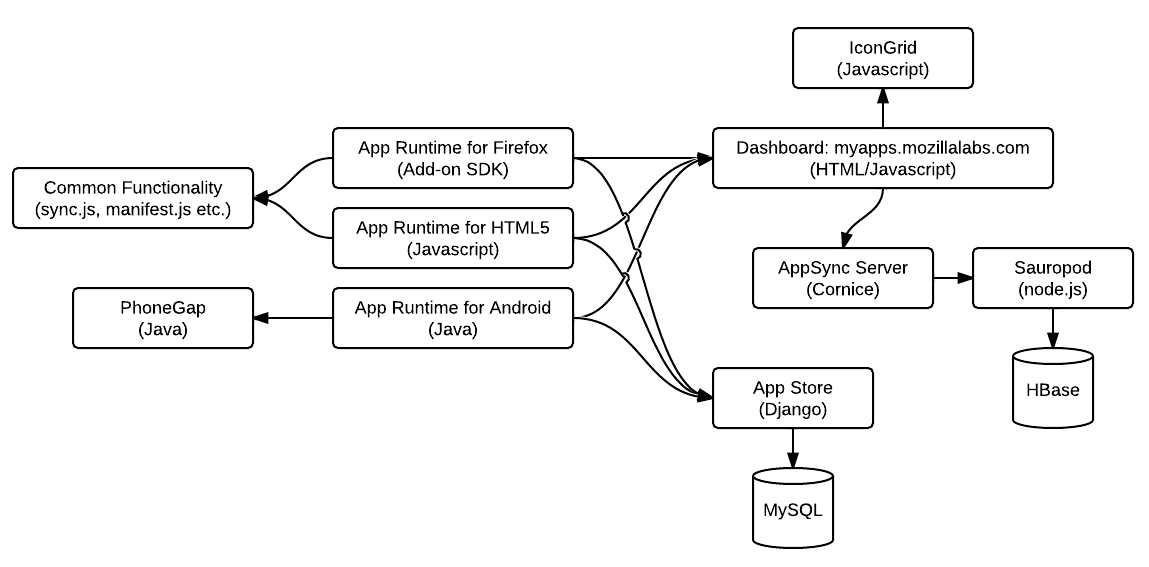

The main repository for the Apps project can be found here. It contains the source code for the HTML5 App Runtime (include.js and trusted.js are the important pieces), the App Runtime for Firefox and the Dashboard that is currently deployed on myapps.mozillalabs.com. The Dashbaord was built using IconGrid, a JavaScript library to build touch friendly scrollable pages. The App Runtime for Firefox is written using the Add-on SDK and shares a few common files with the HTML5 runtime (repo.js, urlparse.js, manifest.js and sync.js).

Source code for the Android App Runtime (codenamed ‘Soup’) can be found here. It is a regular Android application written in Java with an embedded PhoneGap instance to support the marketplace and app launching.

On the server side of things, Zamboni is the code that powers addons.mozilla.org, and was extended to support apps-preview.mozilla.org. It is built on Django. The AppSync server is also written in Python (using Cornice) and is what powers app synchronization across all three runtimes (HTML5, Firefox and Android). The AppSync server in turn talks to Sauropod, written in node.js and backed by HBase. Sauropod is a Mozilla Labs experiment aimed at building a secure storage system for user data. Tarek Ziadé has a more comprehensive overview of how all the server side pieces fit together, which you should go read!

Don’t hesitate to participate and ask questions on our mailing list. We encourage you to play around with the system and file any bugs that you may find here. Together, we can make an open, healthy app ecosystem for the web a reality. We look forward to hearing from you!